What’s the first thing you do when you wake up? Reach for your phone? A bottle of water? Draw back the curtains? All of these things have one strand in common: synthetic polymers, AKA plastics. We open and close our day by laying our hands on plastic. Our relationship with plastics has been an endless saga. We invented them in 1855 and marketed them in 1907. We began using them en masse in World War II, and have gone on to overusing them in the last decade. Now, they are here in the form of microplastics. In our oceans and in us.

Plastics don’t just make our lives convenient. In the world of medicine and technology, they can be life-saving. And yet, they can also put our planet in a chokehold and squeeze the life out of every species in the ecosystem. Thus follows our love-hate relationship with plastics—a dance that we have more or less learned to groove with by now. The question is, what happens when the music stops?

Most of us know and understand the significant perils of plastics. But over time, because we have chosen to push ahead with more plastics instead of regulating our dependence on them, those perils have mutated into newer, more challenging hazards. In the words of my gamer friend, we’ve been playing the game too long, and now we’ve unlocked Doom Level: Ultra-Nightmare.

What are microplastics?

Coined in 2004, ‘microplastics’ are tiny fragments of plastics less than 5 mm in length (the average grain of rice is 7 mm in size). Think of them as the reckless grandchildren of plastics—small, fast-moving, and always leaving a vast mess in their trail.

How are microplastics formed?

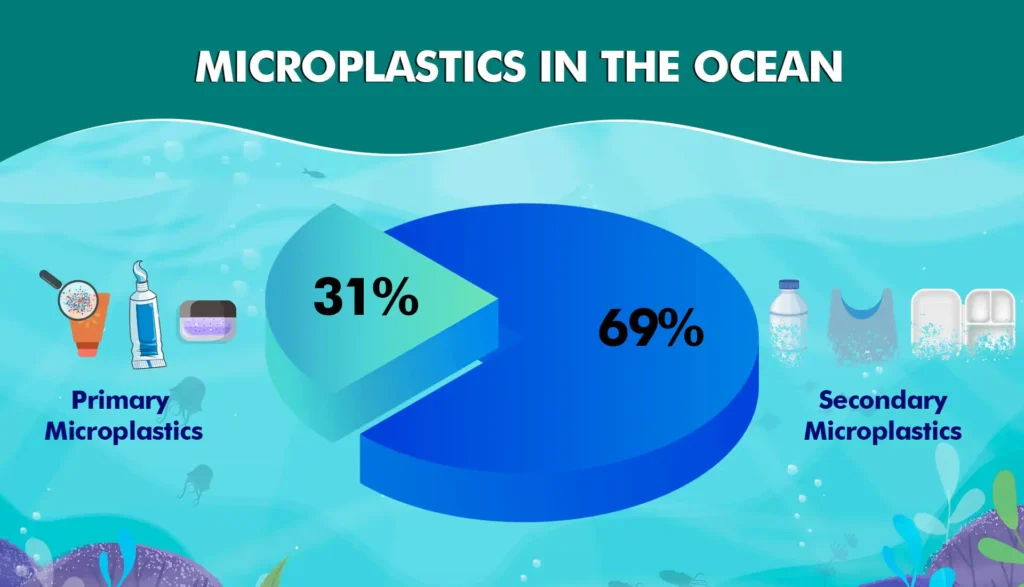

Microplastics come into our lives in two major ways:

- Primary microplastics: These include purposefully manufactured microplastics like the microbeads in exfoliating face washes, toothpaste and other cosmetic products, craft glitter, and the fine stuffing fibres used in plush toys.

- Secondary microplastics: Larger pieces of plastic get broken down by mechanical forces like the wear and tear of repeated use, sun’s heat, ocean waves, and wind waves into smaller particles called secondary microplastics.

How far and wide have they reached already?

It was legal to dump plastic waste into the ocean until the nineties. And after nearly a century of being treated as a surging global junkyard, marine conservationists report that as of 2022, every square mile of our oceans contains 45,000 pieces of plastic. In addition to this, over 20% of the ocean’s plastic waste content is microplastics. Because most microplastics are invisible to the naked eye, they are difficult to account for and control.

Their small size and lightness in weight grants them free mobility in all mediums: water, land, and air; they move most rampantly in water, given water’s dense fluidity. This means it is in our food web, which undoubtedly implies that it is in us. The most popular theory is that they enter our food chain through zooplanktons. Zooplanktons are a community of the smallest microorganisms in water bodies, which feed on bacteria and algae. They confuse microplastics for food, and as bigger creatures consume these planktons, microplastics make their way up the food chain, all the way into our gut! To say that microplastics affect humans would be a gross understatement.

“So what? I can cut out seafood from my diet if I choose.”

It’s not that easy. While microplastics are predominantly aquatic residents, they are not uncommon in other spheres. Researchers have found them in drinking water, salt, honey, poultry and beer, to name a few food sources.

It is no shock then that human tissue samples, blood samples, and waste samples now show the presence of microplastics. Doctors have identified them within the womb, in babies, and grownups alike. A rather popular fact doing the rounds is that we currently ingest microplastics equivalent to the size of one credit card each week!

How can they harm us?

- Microplastics can be abrasive on the walls of internal organs, and these tears can cause bleeds (especially in infants) and leave our organs vulnerable to a range of infectious diseases.

- A vector is any medium which carries illness from one site to another. Microplastics can be lethal vectors when they transport harmful bacteria and micro-parasites.

- Microplastics are known to piggyback on red blood cells, limiting the ability of RBCs to convey oxygen to the body.

- The process of chemical leaching sheds the toxic coating on the microplastics into the bloodstream. This process is especially harmful when microplastics feature trace metals like cadmium and lead. These metals are reactive and can create cancer-causing compounds in our bodies.

- They can also break down further into nanoplastics (great-grandchildren of plastics), which are less than 0.001 mm in size. Nanoplastics cause brain cancer, infertility and hormonal imbalances.

Perhaps the most terrifying fact of them all is that scientists admit that there is so much more that is unknown about the effects of microplastics inside humans.

Is there a way to totally evade them?

There isn’t one. Realistically, we cannot cancel our association with plastics per se. So while microplastics shake up the human world, we can do little to obliterate them permanently. What we can do is attempt to catch the microplastics before they go into the drains in our homes, all the way into oceans. Better yet, we can watch all our future purchases closely for their synthetic composition and make more informed choices as shown below.

Wear Your Responsibility: Read the labels printed on the fabric of your clothes, bed linen and any other textile needs. Organic cotton, linen, hemp, and pure silk are plastic-free, unlike rayon, nylon, and polyester options.

Planet-friendly Playtime: Extend the same caution to your toddlers’ plushies and crafting tools. Today’s market offers a wide organic selection that can replace acrylic paint, polymer clays, and slime.

Glam Right: Makeup products like lip gloss, powder-based palettes, mascara, and nail polish consist of microplastics. With continued use, they can cause micro-abrasions on the skin (especially during makeup removal). Switch these out for zero-waste brands that go easy on the oceans and your skin.

Gatekeepers of the Ocean: Use the finest filters possible in your washing machines to trap plastic microfibres from passing through. Clear out the filter into your plastic disposal system, or store it separately until you can pass it on to your waste handlers.

Carpet Control: Vacuum as often as possible, especially over area rugs and doormats, as microfibres come loose from them with use.

Since we’ve caught the problem (somewhat) early, we stand a chance of getting in front of it and weakening its impact. It all boils down to the vigilant role we are each called to fulfil. So get the word out and keep an eye out.