When I was nearly 12, my mother bought me a fairness cream. She may have thought it would help with my newly emerging acne. Or maybe she thought it would help my tanned skin. In any case, the whispers that had slowly been growing inside my preteen soul suddenly turned into shouts: ‘YOU’RE UGLY! Your own mother thinks so!’ The warped cultural code surrounding me amplified these voices in my head. I’d seen the ads for similar fairness creams at least five times a day. Being tan in these ads usually meant you were also insecure, uncomfortable, or underperforming. Being fairer was the first step to being better, beautiful, and acceptable. These ads and the media at large have come a long(ish) way since. But is it enough? Let’s inspect the media’s colourism problem, especially the depiction of underrepresented skin tones over the years.

Colourism—it’s all relative!

At first, I thought this was a South Asian/Middle Eastern problem since dark-skinned women were all over Western media. As I grew up, I realised that the perception of skin colour varied by region, culture, and ethnicity. For instance, Priyanka Chopra is a brown-skin representative in America. But, in India, she is fair enough to feature in fairness cream ads.

Once you understand this nuance, it is easy to see that the Western media seldom represents dark-skinned African American and Latin American people. In fact, in representations of Black people, casting agents almost exclusively favour a light-skinned Black person. Especially, if they want to show an intelligent, educated character of a dignified background. Just look at the robotics geek Fabiola from Never Have I Ever or Dr Jackson Avery from Grey’s Anatomy. The dark-skinned Black person gets the more (supposedly) “ghetto”, aggressive, stereotypical roles like a single mom from the projects, a gang member, or a drug dealer. Sure, a few movies and shows portray dark-skinned characters in reputed positions. But then, they must come from humble beginnings—like Annalise Keating from How to Get Away with Murder or Cookie from Empire.

The ‘foreign features’ fetish

Ask anyone if the media represents any beautiful dark women, and the first name out of their mouths would probably be Lupita Nyong’o. Nyong’o rose to fame with 12 Years a Slave and cemented her stardom with Black Panther. Today, she is the face and advocate of the campaign for the acceptance of beauty in all colours. But, the reality is that there are not many deep-toned leading ladies who enjoy the recognition they deserve. They have to strive for this recognition every step of the way.

Whatever meagre progress comes about is uneven. Legends like Viola Davis and Octavia Spencer can now open movies and lead TV shows. This is a step in the right direction. Yet, in the modelling world, if you are dark-skinned, you can only hope to make your mark if you look exotic. A dark-skinned model must be thin, with small and ‘interesting’ facial features and complexions, like Angolan model Maria Borges or Sudanese model Nyakim Gatwetch. So it is worth celebrating that even against this backdrop, sweeping strides are being made. The Vienna Fashion Week 2019 saw the Gold Carvier Crew from Nigeria taking over the runway with their norm-defying walk. Models of varying physical attributes, especially skin colour, rocked the ramp, and their videos are still viral today.

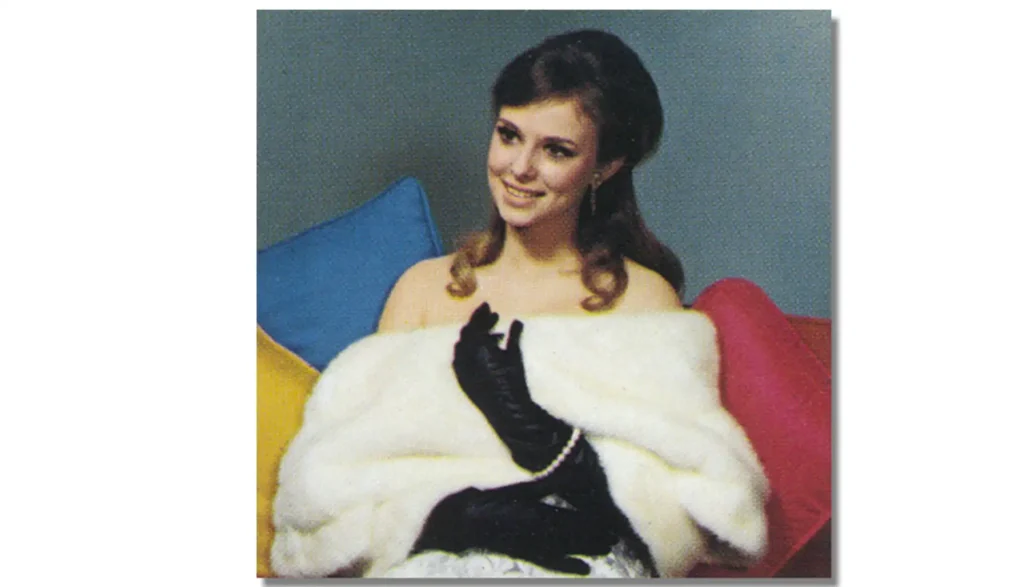

The unfairness of Shirley cards

There’s a technical reason filmmakers prefer lighter skin on camera: Shirley cards. Photo labs working with Kodak printers in the 50s used the photograph of a young white woman named Shirley Page as the standard to calibrate printed photographs’ colour palettes and densities. While the standard now incorporates various skin tones, darker skin still requires extra effort that photographers and cinematographers may not want to put in. The result? Dark skin shows up in poor picture quality.

An episode titled ‘Black Like Us’ from the show Black-ish explores this issue when Diane isn’t lit properly in her class photograph. The conversation leads to Diane confronting her parents about how her racial experiences are different from her light-skinned mother.

In the documentary Skin, conceptual artist and photographer Mudi Yahaya suggests that colourism in Africa has much to do with the Shirley cards. The documentary briefly provides a refresher in history, rewinding to when prospective grooms chose their partners based on photos. They often gravitated toward the well-lit image of the lighter-skinned lady. Thus, people began to consider light-skinned African women more desirable. The documentary also deals with the detrimental effects of bleaching and why women go through such a damaging routine: to keep men in their lives and get better jobs. To them, it’s about social mobility and socio-economic security. So there you have it: a simple card, a severe ripple effect.

The ‘friendly fire’ of colourism

Even within one’s own community, lighter skin begets greener pastures. In his documentary, Beauty and the Bleach, Tan France shares that his experience goes beyond the racism he suffered in Doncaster, England, where he grew up. In his native community, he was raised to believe that skin colour determines not just attractiveness and marriageability, but also social opportunity. The stigma births tasteless jokes like, “they got dark because they ate too much chocolate or drank too much black tea.”

In hopes of distancing themselves from such prejudice, fair-skinned performers, until the 1960s, used to “pass” as white. Latin Americans discovered early on that being considered white led to better opportunities. This remains true to this day.

In his autobiographical book Born a Crime, Trevor Noah talks about his mixed-race appearance turning him into “a chameleon” in people’s eyes. He reveals that he chose to use this as an opportunity to change the world’s “perception of [his] colour” instead of allowing it to change his identity. Stories like Noah’s inspire a powerful acceptance of one’s skin colour in the place of renouncing it.

Against a colourist entertainment industry

More and more self-aware voices are challenging colourist attitudes, particularly in the world of entertainment. Some film industries, in response, only continue to air their ignorance and dismissal of equal opportunities. How else would you explain South Indian cinema’s repeated casting of light-skinned actors? Especially, in a region typically known for deep skin tones? Tamil cinema celebrates dark-skinned men but pairs them with the fairest women India has to offer. The songs in these movies even equate the heroines to milk and the moon. In her campaign “India’s Got Colour”, Nandita Das calls out the colourist entertainment industry by addressing the opportunities denied to dark-skinned people in the country and urges inclusion.

K-pop has also been in the spotlight for the wrong reasons lately, uncovering South Korea’s blatant preference for pale skin. The social media-awakened sensibilities of Gen Z resulted in the dismissal of fan accounts that photoshopped pop icons to make their skin tones appear fairer. And so the battle rages on, unable to oust colourism from the face of reality but still trying.

Wherever you are on the colour spectrum, I’m sure every non-white person has experienced the effects of colourism. The more we talk about it, the better it will get and the more representation we will see. Eventually, we might finally redefine what it means to be beautiful.