With the advancement of technology, journalism has undergone many changes over the years. Of the many changes, this article focuses on two momentous shifts—print to television journalism and TV to online journalism. Both these transitions have many similarities. Accordingly, we will look at them up close to understand how technology in journalism has impacted the industry and the world.

To analyse these changes, we will use three metrics—the ‘what’, the ‘how’, and the ‘how quickly’. These will lead us to two slowly swelling undercurrents that are crucial for us to know.

Print to television

Back when the world relied on newspapers for its daily fix of information, the ‘what’ was determined by reporters and editors who had to make choices about what was and was not newsworthy.

A journalist would hear about an incident, travel to the location, witness it or speak to witnesses, and then go back and write about it. The world would hear about it tomorrow.

With TV, the world no longer had to wait until tomorrow to hear about things happening elsewhere. As technology improved, news travelled faster, making it more important to be the first to report it. This shift resulted in relatively less fact-checking and slightly less in-depth reporting than before. Covering a wide range of news began to matter much more than covering it in depth.

With newspapers, the reader would only be able to read the interpretations of the reporter. With TV, the viewer would still receive a narration. However, it was possible to also see images directly from the source allowing the viewer the possibility of another perspective. Visuals also meant that one did not always have to know a language to get the gist of an incident. The volume of content increased, making the question of who decides which content gets to come on air a little more critical. Revenue, ownership, and advertising began to establish their place at the top of the food chain.

Online journalism

Time went by as it always does, and technology wouldn’t stop improving. In the blink of an eye, nearly everybody could instantly talk to the whole world. They could also capture, create, and share visuals. Suddenly, there was no limit to the question of ‘what’ journalism covers. It was no longer controlled solely by reporters or the wealthy and powerful. The ‘how’ also showed remarkable elasticity by expanding to a previously unimaginable range. The news could now travel by photograph, reel, tweet, narrated content, raw footage, and much more. And, of course, the ‘how quickly’ has become instantaneous. Live streaming can virtually allow a person to see what is happening in another country without delay.

Through the powerful combination of smartphones and social media, anybody could be a journalist. The ‘what’, the ‘how’ and the ‘how quickly’ took on levels that would have been hard to comprehend years before.

The problems of technology-driven journalism

Misinformation

The obvious problem with a system in which anybody can share news is that anybody can share the news. Previous models, though corruptible, had far more checks and balances in place for misinformation. As for more recent models, major tech companies have systems attempting to counter misinformation. Still, they aren’t great and what does exist is primarily for content in English.

Workload

Journalists now have to ensure that they stay relevant and trendy on all the various platforms that exist in order to garner interest. It is no longer enough to have one hour on TV or write an article daily—one must research, write, tweet, post, and share all at once.

Speed of delivery

In a world where everything is instant, being the second person to break the news is the surest path to irrelevance. Therefore, it is crucial not only that one must break the news but also that one must be the first to do so. If not, the world forgets who you are. The need to be first compromises the need to be accurate more than before.

The results of these problems can be lethal—people can refuse vaccinations, storm the Capitol Building or drink bleach—and that is only because of one person in America. This is not a joke.

On Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms, theoretically, if nothing else, the platforms themselves can put curbs in place, and they can control misinformation. But what about private messaging services? Have you ever received a message warning you not to fill your petrol tank in the summer because your vehicle might explode? Or what about something along the lines of drinking a mixture made of cloves, onions, and garlic to ward off the coronavirus? These things can cause damage, and there is no real way to stop them because we are more likely to believe what is sent to us by people we love and trust.

The silver lining of technology in journalism

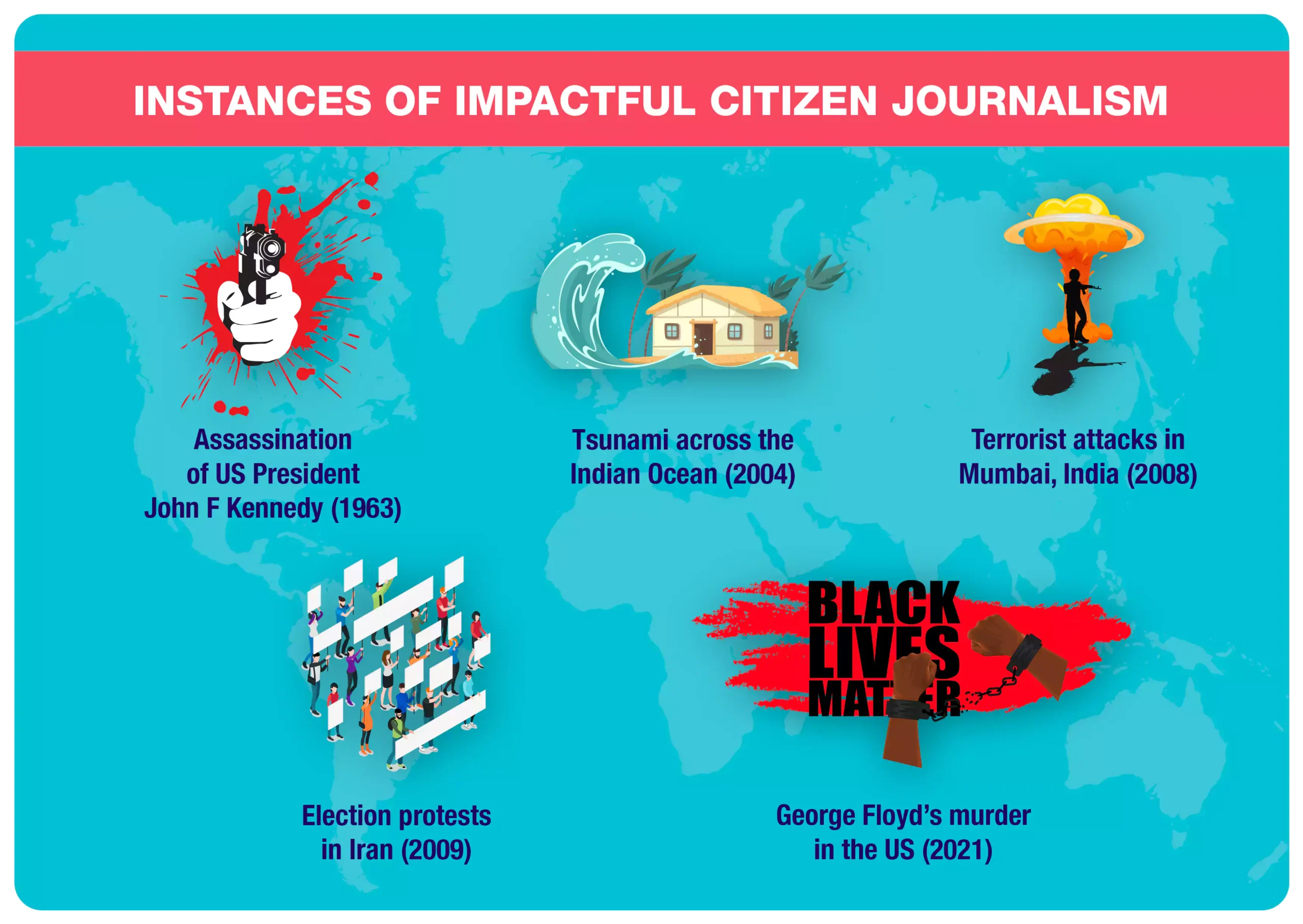

I am not saying, however, that this is some scourge on humanity. On the contrary, some incredibly good things are now possible because everybody has a voice. Citizen journalism allows people to show the world the truth without relying on somebody else’s discretion or interpretation. It also nullifies the dangers of a single story by allowing for numerous perspectives to come forward.

Take Janna Jihad, for instance. The “Youngest Journalist in Palestine” began reporting at 7, when she shared the video of her uncle’s death with the world. She has a voice and is intent on being heard.

Other examples include the people who posted visuals of Michael Brown and George Floyd in the US as the police killed them. These visuals brought masses of people together in protest and made them heard. Hopefully, it will also bring about lasting change in how people are treated.

From the Arab Spring to protests in France, Hong Kong, and India, citizen journalists have often held mainstream media and the wealthy and powerful accountable. Watchdogs, indeed.

The undercurrents echoed by technology in journalism

We must be aware of two undercurrents as we grapple with the sheer volume of news we come across. First, there is an ongoing tussle between the quality of content and the speed of delivery. As the emphasis on being the first to break the news grows, the amount of research and fact-checking that can go into a story will decrease. We must remember that there usually is more to the story than what we hear.

Second, the burden of deciding the truth has moved further towards the consumer than ever before. When a select few were choosing the news, the responsibility of reporting the truth was mostly on them. Now, it is simply no longer possible to believe everything that we read or hear because there is so much that comes our way from so many sources.

If we remember these two things, we are more likely to be critical about the things we come across; to decipher better what is true from what is not.

We leap unfettered into a world where anybody can voice anything. And with its potency to effect both incomparable good and terrifying ruin, it boils down to one thing—intention. Technology has given us the opportunity; now, it is ours to decide what we do with it. We possess in our pockets the ability to do serious good or severe damage. The coin has been tossed—where will it land?