Normal (adj.) - Something that everybody claims to be, and yet nobody would dare define because they wouldn’t fit the bill.

Human minds are different, just as human skin colours are different. But, unfortunately, just as some of us wrongly associate a hierarchy among people based on the colour of their skin, we do so with human minds too. Yet, we all think we are normal. We often recognise traits that are different to our own and then quickly turn them around as less than, as is often the case with neurodivergence. Neurodiversity comes in many forms, such as autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), dyspraxia, dyslexia, synesthesia, dyscalculia, Down syndrome, and epilepsy, among many others. In a sense, neurodiversity encompasses all of them. And yet, neurodiversity is more than just a word.

What is neurodiversity?

Neurodiversity recognises that all human minds work differently—not less than but different. The term refers to conditions in which a person thinks or processes things or even does the same thing in a manner different from the usual. For instance, consider neurotypicals, most of whom can see all the colours in the colour spectrum. In the same situation, neurodivergent individuals might not see blue sometimes but might be able to see infrared.

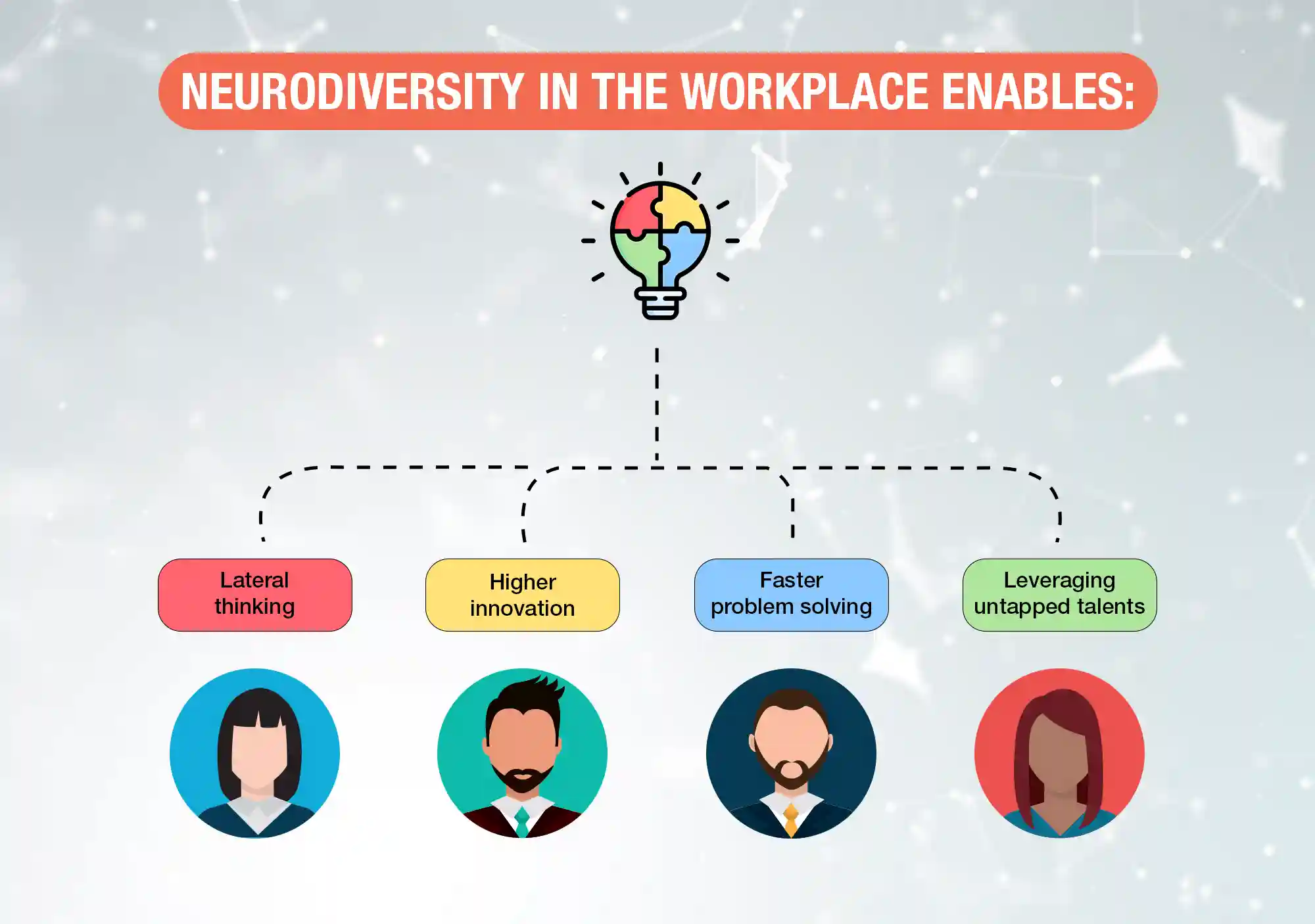

What neurodiversity can add to a workplace

Neurodivergence is no longer treated as a disability—it is just a difference in how the brain works. With this shift, practitioners now view neurodiversity as different ways of learning and processing information instead of labelling them as “illnesses”. A neurodivergent individual can be skilled in other things and see things in ways that neurotypicals simply can not. They bring a myriad of perspectives to the table. They can be incredibly logical and analytical, remembering high volumes of information and possessing the ability to hold large, complex systems in their minds.

Sometimes, they have excellent spatial awareness and can create plans of rooms or buildings in their minds without having to put them down on paper. Mathematics, logic, and dealing with computers often come far more easily to them than things like socialising or communicating.

The flipside of neurodivergence

It isn’t all roses and ponies, however. The downsides of being neurodivergent can be terrible. Heightened senses can mean that everything is stimulating all at once and can often be painful. Sounds are louder, lights are brighter, and sensations are deeper. Imagine trying to write a report in the midst of that.

Dyslexia can make it difficult for people to read or write quickly. In addition, people may use the person’s poor spelling to dismiss their ideas outright.

Dyspraxia can make it difficult for a person to operate some machines or might mean that they knock things over without meaning to.

Sometimes, neurodivergent individuals can be restless and struggle to focus when the task is not sufficiently stimulating. Changes in structure or routine can also be tricky for them.

Social cues tend to be the most difficult to read, making it increasingly challenging for neurodivergent people to socialise even when they genuinely want to.

Now, imagine a meeting with various people present, and one of the lights in the room is flickering a little bit. It’s barely enough to notice but not enough to go through the trouble of calling somebody to fix it. Unbeknownst to the neurotypical people in the room, this might be getting on the nerves of a neurodivergent person. Suppose the discussion in the meeting is not engaging enough or filled with small talk. In that case, the neurodivergent person might get up and walk out. They had no intention whatsoever of being rude or causing a stir, but that is precisely how everybody else is likely to interpret it. Without proper awareness and understanding, it will make for a very awkward workplace after the meeting. Moreover, the neurodivergent person will be entirely unaware of it all.

How can we be accommodative?

Number one on this list must be awareness and understanding. If employers and colleagues know how neurodiversity works, they could create a far better environment for everybody. Let’s be honest—nobody likes to work with flickering lights above them or beside a photocopier that will not be silent.

The office environment could be more accommodating by ensuring that there are no bullies targeting people. Nobody likes to work with bullies. Additionally, modifying the procedures for hiring personnel would allow for more neurodivergent individuals to apply and be given a chance. These initiatives would improve the workplace for everybody involved.

For many neurodivergent people, flexible work timings and the freedom to take breaks can improve their ability to focus on the task at hand. Sometimes, a particular chair or screen may help make them more comfortable. It could be these little things that make a massive impact on the person’s ability to contribute to the work, which, in turn, could vastly improve the overall growth of an organisation.

And that is just it. Being more accommodative is not some gimmick or cosmic collection of karma points that an employer might enjoy by building a neurodiverse workplace. On the contrary, there are actual benefits to the organisation by ensuring that they employ a diverse set of thinkers.

The real tragedy of it all often lies in our general understanding. If you had a problem to solve, would you rather have ten people who thought the same way attempting to solve it? Or would ten people who could approach the problem from different angles be the better choice? Companies often want to stand out among the crowd but rarely want to employ individuals who stand out from others.

The individuality neurodivergence offers

Talking Fingers is the name of a recently published book edited by Padma Jyothi and Chitra Paul. It includes the thoughts and opinions of 16 non-speaking autistic contributors aged from younger than 10 to mid-20s. One of the questions posed to them in the book was about a cure for autism—if there was one, would they take it?

Of the 14 who responded to the question, only one said outright that she would. Almost everybody else said that it was a part of who they are, giving them perspectives and skills that are highly valuable. Of course, if there were a way to get rid of the pain and sensory overload, that would be appreciated, but to rid themselves of the whole thing? They would rather not.

Neurodiversity poses an interesting opportunity for organisations. By making a few changes to the workplace, it can become a space that is easier to work in for neurotypical and neurodivergent people alike. The overall quality of work also improves. It is your move now.

“Neurodiversity may be every bit as crucial for the human race as biodiversity is for life in general. Who can say what form of wiring will be best at any given moment?”

Harvey Blume, The Atlantic, 1998