I am the sort of person who has never really understood or been interested in the workings of economies. However, having heard about the Sri Lankan economic crisis, I was curious. First, I read about the protests that have broken out and the people’s suffering. Next, I decided to try and figure out what happened, why it happened, and whether anybody could do anything about it. If you are like me and do not understand most economy-related jargon, then I will try to simplify it for you. Before I begin the story, let me set the scene.

The background: a struggling economy

This current economic crisis in Sri Lanka is said to have begun in 2019. However, the story doesn’t quite start there. While I will not go through the entire history of Sri Lanka, there are a few things that we need to understand to put all of this in context. Not too long ago, Sri Lanka had a welfare state. For nearly 30 years after independence, the country enjoyed free education, healthcare, and job security provisions. Still, in the late 1970s, Sri Lanka opted for an open economy.

By becoming an open economy, they began to depend heavily on trade. As an island nation, imports would always rack up quite a bill, and the exports would struggle to match it. When a country exports more than it imports, it has a ‘trade surplus’; when the reverse occurs, it has a ‘trade deficit’. The former would mean that the country is making money (based on foreign trade alone), while the latter would mean a loss. The country’s transition to a trade-based economy during the 1970s has contributed to its current state.

Internal conflict in the country also aggravated this situation. A terrible civil war raged from 1983 to 2009, killing tens of thousands and wounding many others. Thus, this internal strife resulted in an already weak economy ambling its way towards the storm that would strike it a decade later.

The secondary character: a people in peril

Everybody knows that a collapsing economy is a bad thing. But until recently, I wasn’t one of those who knew just how bad. If you had followed the news covering the Sri Lankan economic crisis, you would have seen long queues of people waiting to get access to some fuel or cooking gas. I saw those pictures, too, but I never really thought about it. Or perhaps it was just easier not to think about it.

The average auto rickshaw driver cannot move their vehicles because there is no fuel. Without any source of income, their families do not have food, but even if they did get some money, there isn’t any cooking gas for cooking. And if they were lucky enough to get that too, well, what are the chances that they would get hold of some rice and vegetables amidst an agricultural decline? This isn’t a sob story. It is a reality.

The government has very little money left and cannot afford to import essentials such as food, fuel, and other energy sources. In fact, the government has disallowed the sale of fuel for non-essential purposes. In many cases, people cannot get to their jobs or earn a living since fuel is only available for vehicles transporting food and medical supplies. Those who can are encouraged to work from home to save resources, while others are even skipping meals because there simply isn’t enough food.

Education and health

Schools have been closed because the country does not have enough electricity and paper. The government put enforced power cuts in place to save energy. An inability to import medicines has left the healthcare systems reeling, and lives are at risk. But how did it get so bad?

As with things of such a scale, there wasn’t one thing that caused it all. Instead, various factors came together to bring about the dire circumstances of the Sri Lankan economic crisis. The plot just keeps getting thicker.

The main characters of the Sri Lankan economic crisis

This story of the Sri Lankan economic crisis has some notable characters who have yet to make an appearance. So before we examine the factors that caused this crisis, let me introduce these players to you.

Gotabaya and Mahinda

Sri Lankan politics have become a bit of a family business over the last few decades, with the Rajapaksa family in charge of most of the country’s wealth and politics. The two most prominent names in the family are Mahinda and Gotabaya Rajapaksa. The brothers take turns swapping between various posts in the cabinet. Mahinda has repeatedly been President and Prime Minister over the last few decades, while Gotabaya went from the Defence Ministry to the Presidency in 2019.

During their tenure, the Rajapaksas have made some questionable decisions, to say the least. Unfortunately, one of them is pertinent to another big player.

China

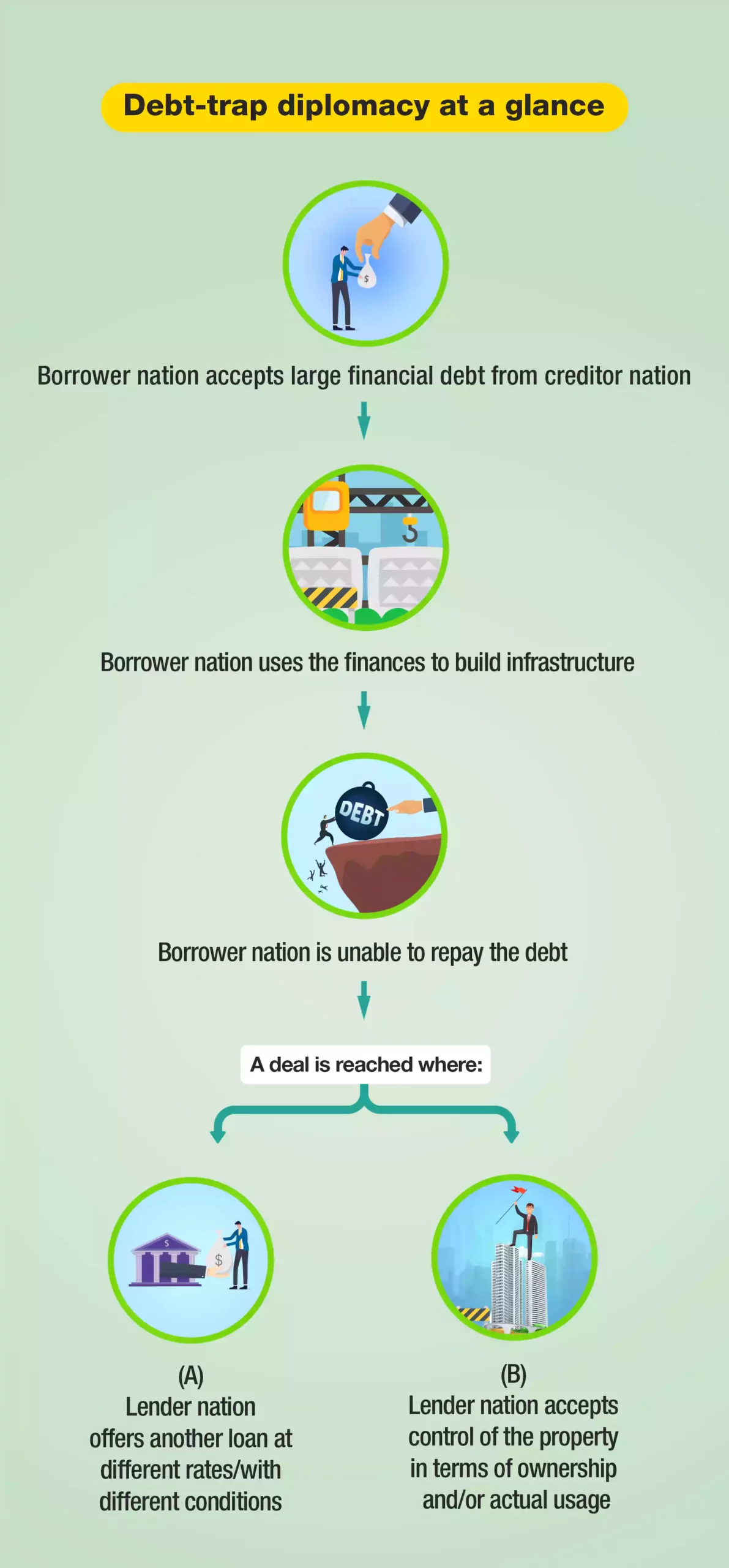

China has been one of the biggest lenders of money to Sri Lanka. But this is not mere borrowing and lending as you and I know it to be. It is “debt-trap diplomacy”. The idea is that a country lends vast amounts of money to another—money that is not easy to repay. The borrower uses it to construct large-scale infrastructure—highways, ports and airports, power plants, etc. However, when the projects fail to bring back enough money to pay the lender, a deal is reached that allows the lender to take control of the property instead.

The Chinese are masters of debt-trap diplomacy, and Sri Lanka’s Hambantota International Port is a perfect example of this type of diplomacy. The port cost Sri Lanka $1.3 billion to build, with the help of a loan from China. When the port could not recuperate the money necessary to repay the loan, the government decided to privatise a majority stake. After negotiations, the Sri Lankan government sold a 70% stake in the port to a Chinese company called China Merchants Group Limited. Furthermore, Sri Lanka leased the port to the Chinese company for 99 years.

Russia and Ukraine

Gotabaya and Mahinda Rajapaksa blamed two things in particular for the Sri Lankan economic crisis—the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And while it is blatantly untrue to state that they are the sole contributors to the situation, they are factors.

Sri Lanka has a vital trade relationship with both countries. Together, they buy roughly 18% of Sri Lanka’s black tea exports. It is also true that 45% of Sri Lanka’s wheat imports come from them, and over 50% of its sunflower oil and seeds, soybean, and peas come from Ukraine. However, as the war continues, it is increasingly expensive to import these things from Ukraine and Russia or elsewhere, as those two nations also supply them to many other countries.

Now we know the key players in this story. We also have a rough idea of the background to these events that have unfolded. In the sequel to this article, we will look into further detail about how and why this island paradise is beginning to look more and more like a Greek tragedy.