In the previous article, we began looking at the story of the Sri Lankan economic crisis and how things had fallen apart so badly. We have met all the major characters and touched briefly upon what the scene is like now. Now, we examine the other plot twists. While the factors that led the country into this mire are no mystery, we have yet to cover the central theme of this tragedy: painful irony. So, let’s dive right back in.

The rise of foreign debt

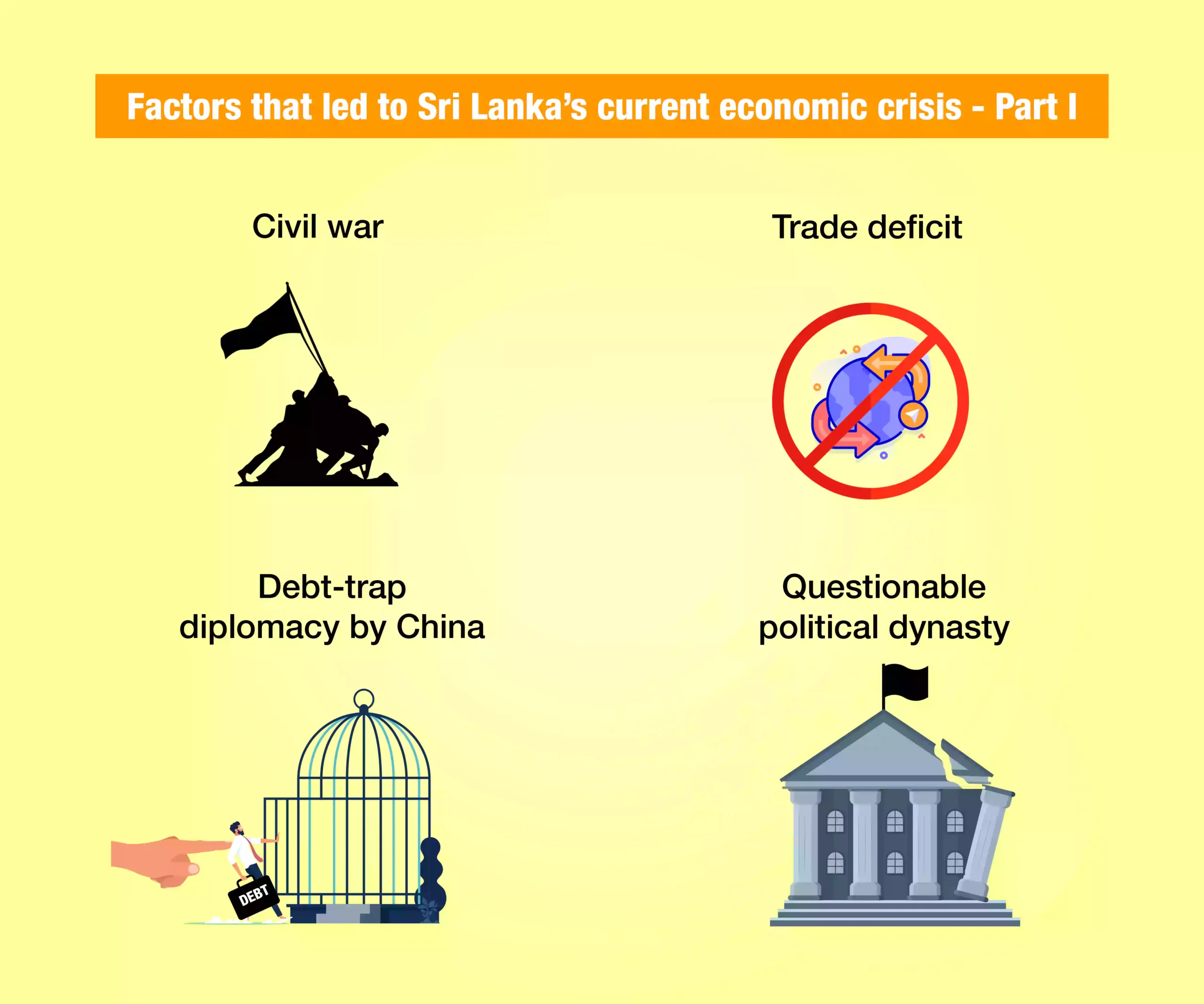

Since we have already touched upon this subject, let us examine it as the first of the factors that led to the current Sri Lankan economic crisis.

As a nation with a trade deficit (when a country has more imports than exports), Sri Lanka is constantly looking to provide for its people using loan money. It is over $50 billion in debt and cannot repay it. Not only does the country have very little money left, but there are now fewer ways of making more. Additionally, the island owes a large part of this debt to China.

In April 2022, the country defaulted on its loans, saying it could not repay its creditors until the situation improved.

The fall of tourism

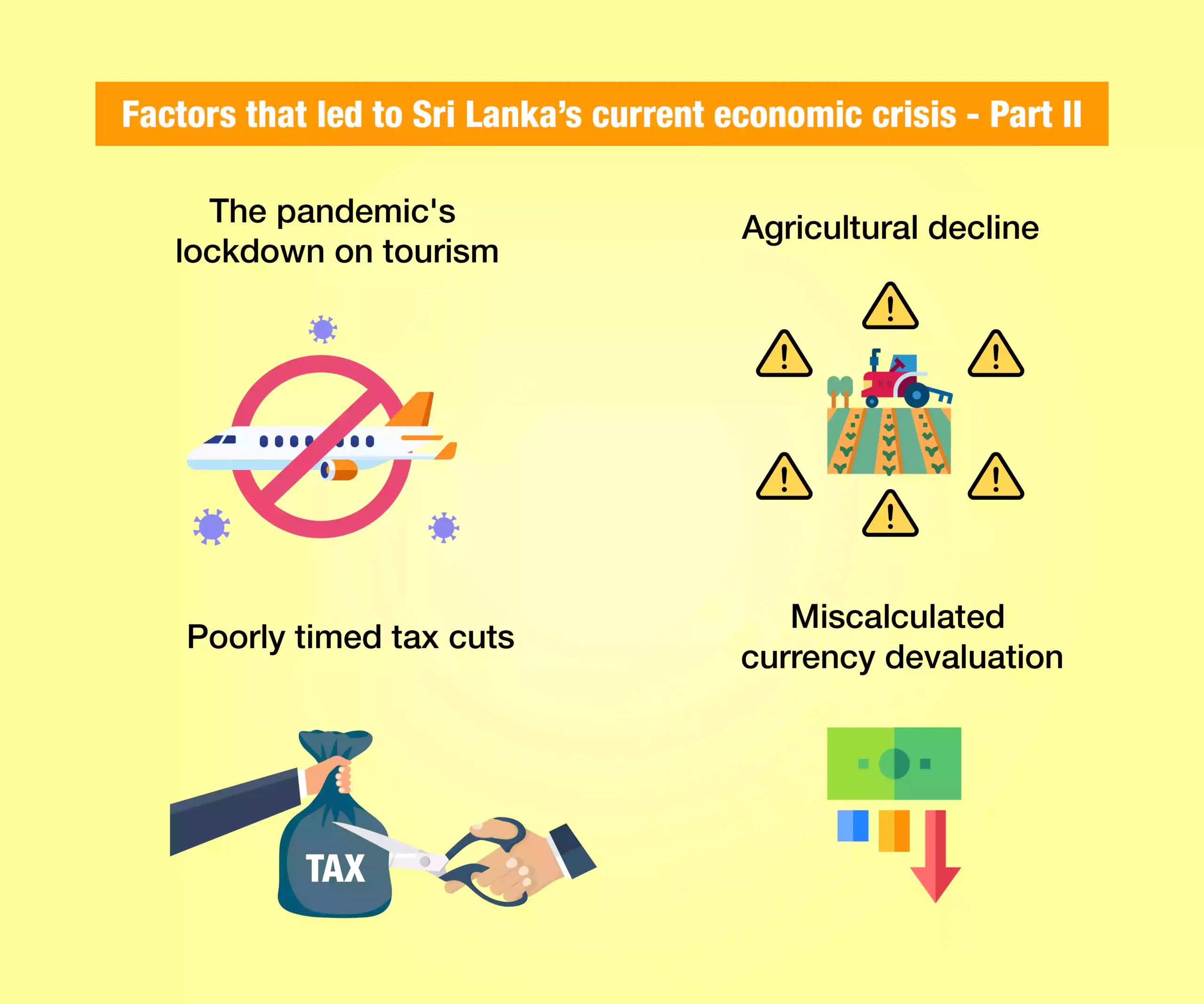

Tourism makes up 12% of the country’s GDP. 2018 was a record year with over 2.3 million tourists visiting the Pearl of the Indian Ocean. As a country with immense natural beauty, Sri Lanka relies heavily on tourism as a source of income. However, since 2018, two factors have contributed to a massive decrease in the number of tourists entering the island.

The first, of course, is COVID-19. The spread of the pandemic and the enforcement of lockdowns made it difficult and dangerous for people to travel. This was a significant blow to tourism industries all over the world.

The second factor occurred in 2019. On Easter Sunday, a local militant Islamist group attacked three churches and three hotels in three of Sri Lanka’s cities, including the commercial capital of Colombo. The attack claimed over 250 lives and injured hundreds of others. Forty-five of the people killed were foreign nationals. Between the pandemic and the fear of attack, tourism in Sri Lanka suffered greatly. In turn, the Sri Lankan economic crisis worsened.

Tax cuts: the red herring

In a bid to come to power in 2019, Gotabaya made certain promises—most notable of which was the idea of tax cuts. He promised enormous tax cuts, and when put in place, they were the largest the country had ever seen. Gotabaya’s government slashed VAT by nearly 50%. In addition, it removed seven other taxes in a move that decreased the number of tax-payers in Sri Lanka by around 1 million. And if that seems like a lot, it is worth knowing that before the tax cuts, the country had only 1.5 million tax-payers.

Consider this for a moment. While the idea of tax cuts seems enticing, the country is billions of dollars in debt and taxes are a large source of income for the government. Cutting taxes in the face of such debt that the government needs to repay soon is like shooting oneself in the foot at the starting line of a marathon.

In theory, tax cuts can result in the economy improving. If people pay less in taxes, they are likely to spend more elsewhere. The government announced these tax cuts on December 1, 2019—only three months before a virus forced the country into a lockdown, preventing people from spending as much. But even without the ill fortune of timing, these decisions were an extraordinary gamble—a bit like the bales and bales of straw that broke the camel’s back.

Agricultural reforms: a false narrative

Let’s stay with Gotabaya and Mahinda for a minute. Another astonishing decision the government took was to ban agrochemicals overnight. This decision aimed to make Sri Lanka the world’s first country with fully organic agriculture (another campaign promise). However, the suddenness of the decision turned the agricultural sector on its head.

Of all the products that Sri Lanka had to import, rice wasn’t one of them. It was self-sufficient in its production of rice. Yet, within six months of the ban, Sri Lanka had spent roughly $450 million on rice imports. Another major export, tea, also saw its crop devastated by the decision.

Let’s get something straight—organic farming is terrific for the health of humans and the environment, but this move requires tremendous planning. It needs to be a slow and careful process because, at least initially, organic farming is less efficient. Produce can be 20-30% lower. With Sri Lanka’s crops failing, its exports suffered, and it became necessary to import rice in order to feed its 22 million people.

The anticlimax: devaluing the currency

The country needed desperate action with rising debt, depleted foreign reserves, and a falling income. So, the government decided to devalue the currency. Devaluation of currency is when a country intentionally lowers the value of its own currency.

This devaluation can result in a decreased trade deficit through increased reliance on local products and boosted exports. Let me explain: when I devalue my currency, I can do less and less with each unit. For example, assume that 1 SLR was equal to 1 USD. If before devaluation I could buy a loaf of bread with 1 SLR, after devaluation, I might need 10 SLR to buy a loaf of bread, but it would still only cost 1 USD.

If my country has a high trade deficit (i.e., more imports than exports), it would be a good idea for me to examine its implications for my economy. By devaluing my currency, I make my products so cheap that other countries would want to buy more, increasing my exports. It also means purchasing things from other countries would cost more, decreasing my imports.

The particular method Sri Lanka adopted to devalue their currency was to print incredible amounts of money. They flooded the market with trillions of SLR in the hope that it would boost exports and encourage people to buy things from within the country. What happened instead was inflation. While the official statistics record inflation of 21.5%, a professor at Johns Hopkins University pegged it at closer to 132%. Thus, the essentials of life became scarce and what was available was incredibly expensive.

The reaction: a precarious cliffhanger

The immediate and most significant consequence within the country was protest. Mass protests have broken out and continued for months, with people demanding resignations within the government and serious emergency action. In April 2022, Mahinda stepped down as PM, and a few months later, Gotabaya followed him out the figurative door after images of protesters storming his literal doors spread across the globe.

Sri Lanka has reached out to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to seek a bailout. Still, those usually come with conditions that can force a government to make policy decisions that they wouldn’t ordinarily make. The other option was to reach out to China for other loans, which might further cripple the country’s treasury. Caught between a massive rock and a very hard place, Sri Lanka now relies on the goodwill of other countries, such as India. India has extended aid to Sri Lanka on relatively more straightforward repayment terms.

Large loans poorly spent, accompanied by imprudent decisions about making money to repay the loans and grow the economy, have left the island nation in dreadful despair. Nobody knows how this story of the Sri Lankan economic crisis ends yet, but, for the moment, Sri Lanka’s prospects look bleak.