If this is your first Around the World article, I’m here to let you know that this series has a unique objective. It is to explore the out-of-the-ordinary ways of countries that don’t typically feature on people’s radars. Case in point: Rwanda.

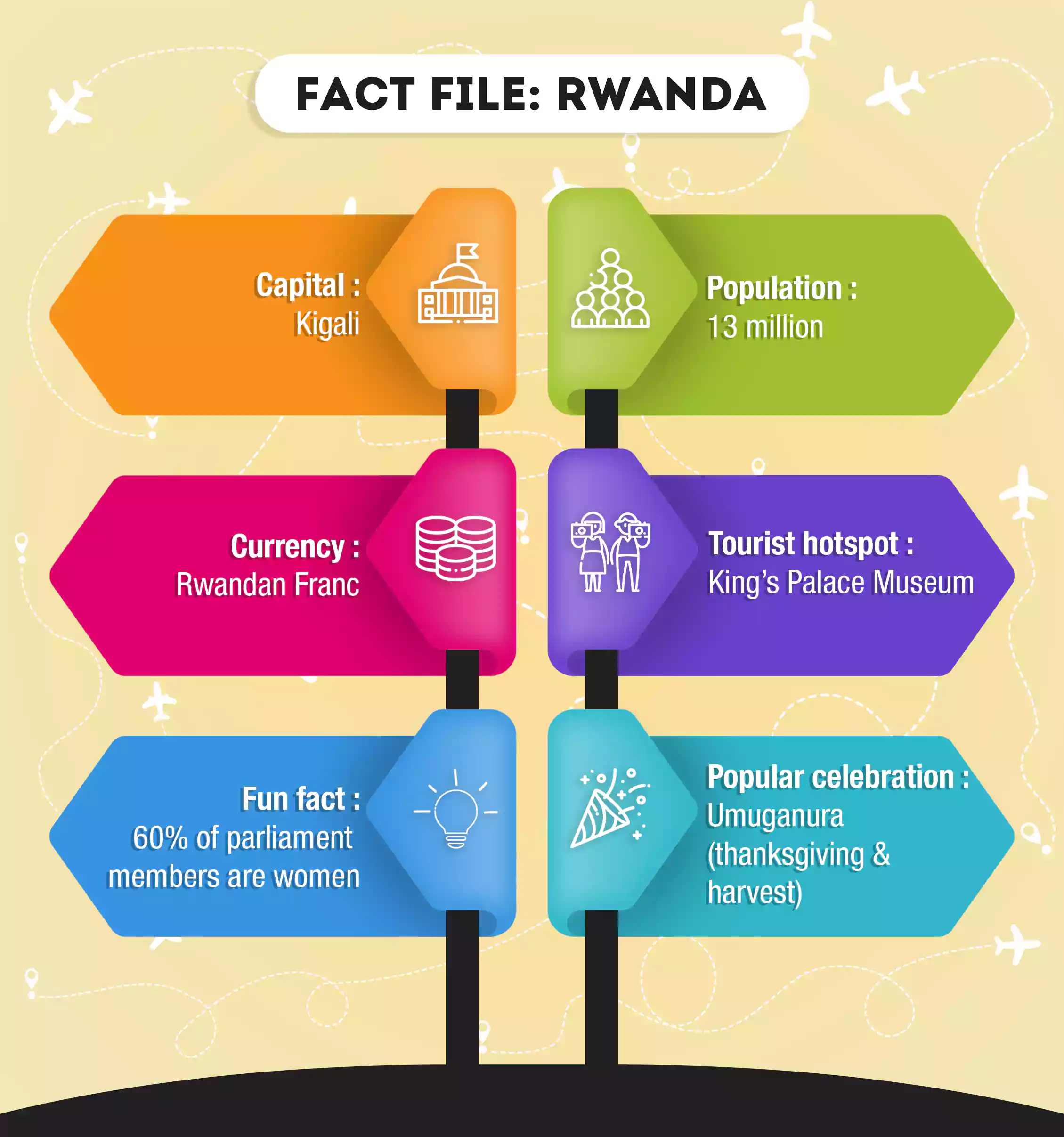

The ‘land of a thousand hills’ is a landlocked nation in East Africa and neighbour to Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Rwanda is the second most densely populated country in Africa. Kinyarwanda, Swahili, French, and English are the four main languages. With this barrage of information, you may feel I am rushing through some facts before I get to something extremely significant. If you thought so: you’re right!

Arguably, the most defining moment of Rwanda’s history and future occurred in 1994. Many things that preceded it and most of what followed are linked causally. Over 100 days in the middle of 1994, certain portions of the population were targeted and killed. It is hard to find exact numbers, but it is estimated that between 800,000 and 1,000,000 people died.

Rwanda’s ethnic groups: the Hutus, the Tutsis, and the Twas

In 1994, the population of 7 million Rwandans could be categorised into three groups—the Hutus formed the vast majority (85%), the Tutsis accounted for roughly 14%, and the Twas made up the remaining 1%. The problems between these classifications are almost immediately apparent. First, there is very little to distinguish between the Hutus and the Tutsis. The Twas were the original inhabitants of the land. Following the arrival of other people groups, the Twas were driven further and further into the forests. The Hutus were predominantly farmers, and the Tutsis owned cattle.

When the Europeans (Germans and Belgians) controlled the area, they sought easy ways to gain without investing considerably. They decided to rely on a specific group of natives to rule for them. Unfortunately, the distinctions amongst the people were minimal. So, the Europeans began to strengthen the divisions. They imagined themselves at the top and then divided the others based on physical features. Thus, the size of their noses, lips and faces became markers of hierarchy. They believed that the Tutsis (also the ruling class at the time) with thinner lips, longer noses, and narrower faces looked more Caucasian and favoured them. Thus, all those with similar facial features became grouped as Tutsis. And those with thicker lips and shorter noses were clubbed together as Hutus. The colonisers gave out identity cards to every person. This system favoured the Tutsis on each front, prioritising them for everything from education to wealth to politics.

Even after independence in 1962, this did not change. On the contrary, resentment towards the Tutsis grew. It finally boiled over in 1994, resulting in the genocide. The genocide instigated by extremist Hutus killed thousands of Tutsis, moderate Hutus, and Twas.

Post-1994 Rwanda

After seeing over 10% (conservative estimate) of its population wiped out, Rwanda embarked on a journey. One that few others can claim to have undertaken. The country took significant steps to ensure that nothing of the sort would ever happen again. They instituted the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission in 1999 and Rwanda Vision 2020 in 2000 to lay out a plan for a concerted effort toward peace and progress. Here are some of the measures rolled out to achieve those goals.

Livestock for a livelihood

The state decided to employ girinka, which means “one cow to every poor family”. This policy attempted to address a severely impoverished and malnourished population by providing them with a means of income and food. The programme has also improved the country’s agricultural production. Furthermore, using manure as a natural fertiliser is a cost-cutting measure. It has even reduced the impact of rain on crops because of its purpose as an erosion-resistant agent. This particular property of manure benefits those who live in hilly areas since the soil often suffers rain-induced run-off. On the whole, girinka has not just advanced economically backward classes; it has also helped the environment.

A graded-up education system

Rwanda poured a great deal of money into constructing schools. The country ensured that education—with a primary focus on ICT education—was comprehensive and practical. They worked towards increasing enrollment in schools for all children. And it seems to have paid off: their primary school enrollment rate, as of 2022, sits at nearly 95%. However, they seem to have created a new problem—they have too many highly qualified personnel for too few jobs.

Gender equality regained

During the genocide, approximately 150,000 to 250,000 women were raped. Gender equality and the way society viewed women was something that Rwanda decided to address. The government has already laid out the goal in Rwanda Vision 2020. They wanted more women in both tertiary education and decision-making positions.

In 2020, 61.3% of Rwanda’s parliament was female. Additionally, the country had seven female Supreme Court Justices out of 14 as of 2019.

A clean slate means a clean state

Umuganda is the idea of community participation or “coming together in common purpose to achieve an outcome”. On the last Saturday of every month, all the citizens of Rwanda come together to participate in community work. This community participation could include cleaning an area, helping to construct something, or repairing public facilities.

Since it brings together all the people in one gathering, umuganda is a hub for communal bonding. First, neighbourhoods unite to discuss their lives and exchange stories. Afterwards, the people conduct a village hall meeting to discuss the region’s critical issues. The practice of umuganda was put on hold during the pandemic but has since resumed through popular demand.

When they say everybody, they mean everybody! From the President to an ordinary civilian, all those who can participate must do so. Failure to participate in umuganda can result in a fine.

Acknowledging what happened

Having implemented all these social programmes, the people of Rwanda realised something important. They needed to acknowledge the past to truly forgive, come together, and move forward as a country. There could be no avoiding the subject of the genocide. Any attempt to ignore or not talk about it would stunt the rebuilding process. And so the government established museums and monuments. They have been set up all over the country to inform and remind people of the terrible things that occurred.

Today, survivors of the genocide are still offered social benefits and subsidised living. In addition to rebuilding destroyed homes and infrastructure, Rwanda actively pursued peace efforts. It even became illegal to alter the facts of the genocide or to deny it altogether.

Rwanda: the Singapore of Africa

President Paul Kagame stated that Rwanda wanted to become the “Singapore of Africa”, and they are getting pretty close. The capital city of Kigali is the cleanest in Africa. The country banned plastics altogether—neither production nor import is allowed. They have car-free days when cars are kept off the streets entirely, and people walk, jog, run, or use bicycles.

In an effort to attract investors and companies, the country makes doing business extremely easy. As a result, Rwanda is ranked second on the continent in the ‘Ease of Doing Business’ list by the World Bank. It also consistently ranks among the safest and cleanest places to live.

Unfortunately, these aren’t the only ways Rwanda is beginning to resemble Singapore. The country isn’t big on certain democratic freedoms, either. The press, speech, and assembly have limited protection from the government. It is still officially a democracy. However, a constitutional amendment removed the two-term limit imposed on presidents and allowed Kagame to contest again. Many credit Kagame, a controversial figure in Rwanda, for leading the country out of its conflict and crisis. Nonetheless, many others regard his administration as repressive. In 2017, Kagame won the presidential election for a third term by getting 99% of the votes.

The UK and the refugees

Most recently, Rwanda has been in the news regarding its deal to welcome illegal immigrants or asylum seekers from the UK. Various groups, including the United Nations, are concerned about Rwanda’s track record in terms of human rights. They have heavily criticised this move as violating an asylum seeker’s right to approach a host country of their choice. How successfully would a non-African refugee be able to integrate themself into Rwanda? How safe can Rwanda be for refugees, given recent reports of tensions between them and the host community? All these doubts invite speculation over the country’s intentions. A refugee-hosting country, after all, stands to gain many diplomatic advantages and economic aid. And Rwanda’s reliance on foreign help is not unknown.

Of course, some states have also drawn inspiration from the UK-Rwanda deal. Deals such as this offer potential for improved international relations. They also provide timely solutions for countries which are overwhelmed with asylum-seekers. So the question of the hour remains whether Rwanda is revolutionising diplomatic deals or disrespecting refugee rights.

Rwanda’s new tomorrow

This article barely even begins to cover the complexities of this country. And many people have different opinions about Rwanda, its past, and its future. However, the fact remains that over a period of only 27 years, the Rwanda of today is markedly different to the one that first splashed onto the front pages of world news in 1994. And if it is true, then the story of Rwanda is one of the brightest the world has ever seen.