It would be a gross understatement to say that electronic devices have become indispensable in our lives today. These devices have made our lives enormously easy, from ordering food to flying aeroplanes. Behind every click is a web of communication between networks. And behind these communications are little chips busily giving off signals and transferring data. These microchips, also known as integrated circuits (ICs), or semiconductors, make electronic devices smart. Both the production and delivery of many of our essential goods and services depend on these devices. Any disruption in the global semiconductor supply chain would thus be catastrophic for the world economy. But, unfortunately, that is precisely what has been happening for the past couple of years.

We’ll look at how this happened and which industries feel its impact the most. But before we do, it helps to understand the basic mechanism of a semiconductor, so here goes:

Semiconductors 101

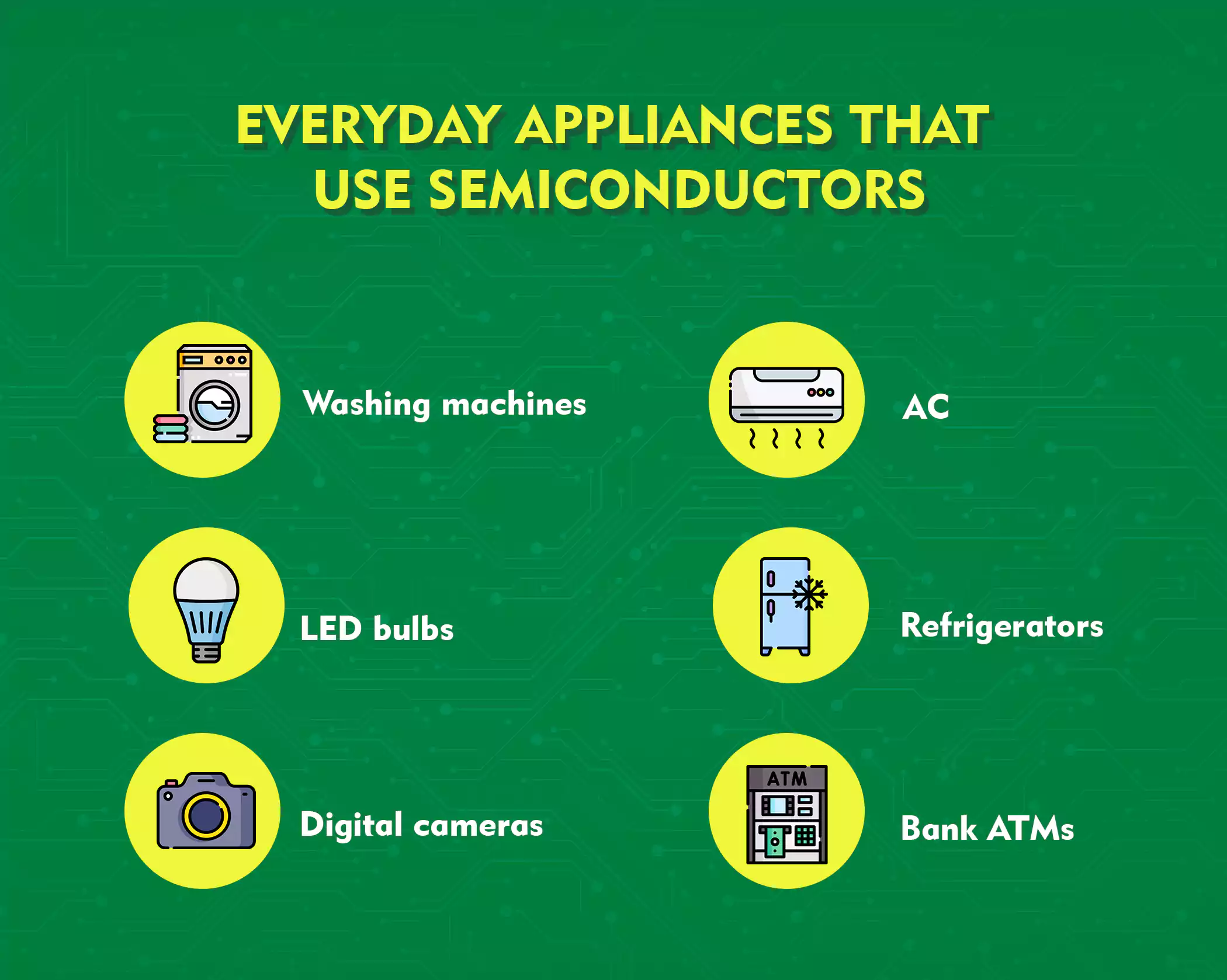

Semiconductors are materials made from pure elements, mainly silicon or germanium. These materials conduct electricity between insulators (or non-conductors), such as ceramic, and conductors, primarily metals. Through a process called doping, it is possible to manipulate the degree of conductivity of a material by injecting pure semiconductors with small amounts of impurities. As the brain behind most of the technology we use today, they play a critical role wherever computing is involved.

Before there were semiconductors, there were electron tubes or vacuum tubes. They would regulate the flow of current in early devices like first-generation computers. However, the cost of operating these was exorbitant since they consumed high voltages of power supply. And in cases of poor welding, gas leakage in the tubes was also possible.

Thus came the semiconductor, a saviour in its own right. Shockproof, cost-efficient, a virtually inexhaustible lifespan—it had a lot to offer. Moreover, with its fast response rate to electrical signals, the semiconductor guaranteed quick ‘on’ and ‘off’ functions and came into wide usage. Quicker ‘on’ and ‘off’ means the speed of processing and computing in your smart device is greater. And that is how semiconductors became the technological beacon for modern living.

Okay, now we’re all set to explore the ongoing problem.

Twin blows: the US-China trade conflict and the pandemic

Almost immediately after Donald Trump became President of the United States in 2016, he began his crusade against the dominance of China in global chip production. The Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) projects that China will lead global chip manufacturing by 2030. With the US accounting for just 12% of global chip production, the need to mitigate the Chinese threat was palpable.

In September 2020, the US Government imposed tight restrictions on exporting integrated circuits (ICs) to the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), China’s largest chip maker. Both sides felt the effects of this decision. In the US, large semiconductor manufacturers, such as Intel, could not meet the demand for chips by themselves. In China and elsewhere, companies dependent on SMIC for chips were forced to source them from other suppliers. With production costs skyrocketing and demand for electronics soaring, prices have inevitably reached new heights.

Adding to these woes was the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. The strict lockdowns and severe restrictions on the movements of materials and people led to the shutting down of several chip-making facilities. As production halted, global supply chains suffered, and the semiconductor shortage worsened. The present scenario is not very hopeful either. According to a recent statement by US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, the ongoing shortage of microchips is likely to continue till 2023 and part of 2024. Pat Gelsinger, the CEO of Intel, also expects the chip shortage to last until 2024 before it recedes. The primary reason for this is the shutdown of operations of major suppliers in Asia. At the same time, the demand for electronics continues to grow.

Even though several industries have struggled due to these supply shocks, some have had to bear the brunt more intensely than others. Let’s take a look at two of them.

(i) Semiconductor shortage in the automotive industry

Car manufacturers have become increasingly reliant on semiconductors to equip their vehicles. Technologies such as navigation, driver assistance systems, and parking sensors have made semiconductors critical to vehicles. The auto industry was already plagued with stalled production and supply chain disruptions before the pandemic began. Trump’s sanctions on SMIC pushed automakers in the US and elsewhere to bring their assembly lines to a halt. In January 2021, Ford, Toyota, and Subaru had to reduce production in the US. European auto giants Fiat Chrysler and Volkswagen have also been adversely affected by this sudden supply shortfall of chips worldwide.

Just like it did with the semiconductor manufacturers, the pandemic also harshly impacted the auto industry. After the outbreak erupted in 2020, large automakers like Fiat and Volkswagen closed down their plants across Europe and the US. Two years into the pandemic, the situation has more or less remained the same. Markets and businesses associated with the automotive sector are still suffering from spill-over effects. In India, for instance, the impact was felt by auto component manufacturer Bharat Forge. They reported in May 2022 that the lingering threat of COVID resurgence and geopolitical tensions had made sourcing raw materials difficult for chip makers. Consequently, input costs and inflation are on the rise. Furthermore, with the demand for electric vehicles (EVs) showing strong growth, automakers will have to develop innovative solutions to survive the current chip crunch.

(ii) Semiconductor shortage in the gaming industry

Semiconductors drive all aspects of gaming, from virtual reality (VR) headsets to consoles. Therefore, it is not surprising to know that the global chip shortage has catastrophic impacts on the gaming industry. While the demand for video games surged during the lockdown period, choked supply chains subdued console makers from meeting this high demand. In September 2021, Xbox head, Phil Spencer, predicted that console supply woes would continue well into 2022. Chip manufacturers and gaming giants are still sceptical of the situation improving anytime soon. Understandably so, considering they have all felt the repercussions of the shortage.

In January 2022, Sony announced that it would continue producing PlayStation 4 instead of PlayStation 5. The unavailability and lack of component supplies for the advanced chips of PS5 have clamped their production. Even its stated goal of producing 22.6 million PS5 consoles by April 2022 was deemed fantastical by investors. Nintendo also announced in November 2021 that it expected to sell only 24 million consoles in 2022, lowering its initial forecast by 1.5 million.

Is there a way out of the semiconductor shortage?

The massive reliance on microchips has proven detrimental to manufacturers around the world. As a result, there is a great need for robust, long-lasting solutions. Research to find alternatives to silicon is already underway. For instance, in September 2019, researchers at Texas Materials Institute published an article in the Journal of the American Chemical Society stating that antimony, a 2-dimensional material, can be a potential replacement for silicon. The high mobility of antimony could drastically increase computing speed and boost a chip’s storage capacities. Another permanent replacement for silicon chips is quantum computing. Quantum computers can harness the principles of quantum physics to achieve high-speed processing through ‘qubits’, which will be significantly more powerful than silicon semiconductors.

From a business standpoint, a few options are available for chip manufacturers to tide over the current shortage. Consider the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) suggestions. The organisation recommends that chip companies enter more merger and acquisition (M&A) deals to expand their production, diversify their distribution networks, and enhance procurement capabilities. The current crisis is an excellent opportunity for firms, governments, and research organisations to invest in finding alternative technologies to ease the effects of political, economic, and natural factors.