Towards the end of July 2022, Pope Francis was in Canada. The purpose of his visit was to meet with indigenous people of Canada, including members of the Inuit, Métis peoples and the First Nations. He wanted to apologise for how the Church treated these people throughout history. Various people appreciated this immensely. However, there was also some cause for discontent, as many were not sure this gesture was enough. We are all familiar with this issue: we have been on both sides of an apology and likely seen ones that weren’t enough. So I thought it was worth spending some time thinking about it.

The Pope’s apology

The stories of the treatment of indigenous peoples everywhere are eerily similar. Almost everywhere you look, you find the same themes: foreign disease, misuse of trust, schools set up to assimilate, murder, and genocide. Canada was no different. This treatment was primarily what the Pope apologised for—and he did, for the most part.

The discontentment with the apology stems partly from the fact that he criticised but did not rescind the ‘Doctrine of Discovery’. This doctrine was a papal concept that allowed colonisers to seize land that Christians did not own. They considered land belonging to indigenous peoples (whom they thought to be savages) as terra nullius or nobody’s land. The Church encouraged European colonisers to claim this land in the name of God. The idea that claiming indigenous land was righteous and legal is the foundation of the attitudes toward them throughout history. To hear the Pope rescind it would have meant a great deal to many people.

While Pope Francis discussed the ordeals that thousands of children went through in residential schools, he did not explicitly call it genocide. However, he used the term ‘genocide’ during an interview on his way home. This instance shows that specific words are incredibly crucial in an apology.

Why we don’t apologise

Emotions

Humanity shares a problematic relationship with emotion. We hide, deny, manipulate, revel in, succumb to, and eventually are ruled by it. We even try to demean emotion by seeing it as substandard to reason and intellect. But, no matter how hard we try, we cannot seem to shake it. The idea that if we ‘control our emotions’, we will ‘succeed’ is widespread. Unfortunately, people often distort it to mean “suppress our emotions, and we will succeed”. For most people, it is possible to get some space to function in the short-term by pushing things down and refusing to allow themselves to feel. However, this process is almost always destructive in the long run.

I mention this because apologies tend to have more to do with the proverbial heart than the mind. We apologise when we have done something wrong. Fundamentally, we don’t like to be wrong. As human beings, we would like to believe that we don’t make any mistakes and are above it all. Unfortunately, that is not how life works. And a sincere apology requires us to be vulnerable, and it often includes some guilt. Making an apology is also a risk because there is some worry about how the other person will react. That is a potent cocktail of emotions.

Then, of course, to make matters worse is the idea that too much apologising could make the person feel insufficient and worthless. So, it isn’t surprising that people don’t like to apologise, is it?

Words, words

Many people struggle to apologise because they do not think they have the right words to do so. However, more often than not, an apology needs the right intentions more than the right words. If it is genuine, it is far more likely that people will receive it well.

Pride

Another reason why people don’t usually like to apologise is that they perceive it as a matter of lost pride. As the ‘head’ of the household, many husbands never apologise to their wives or children (the others are, I guess, the feet and tail and whatever else bodies tend to have). So, no matter what he does, he cannot be seen as having lost face.

This fear of losing face is often why people in power lie and deny their actions multiple times before finally being forced into apologising. Unfortunately, what results is an apology that is disingenuous and that usually only serves to make things worse.

How to apologise

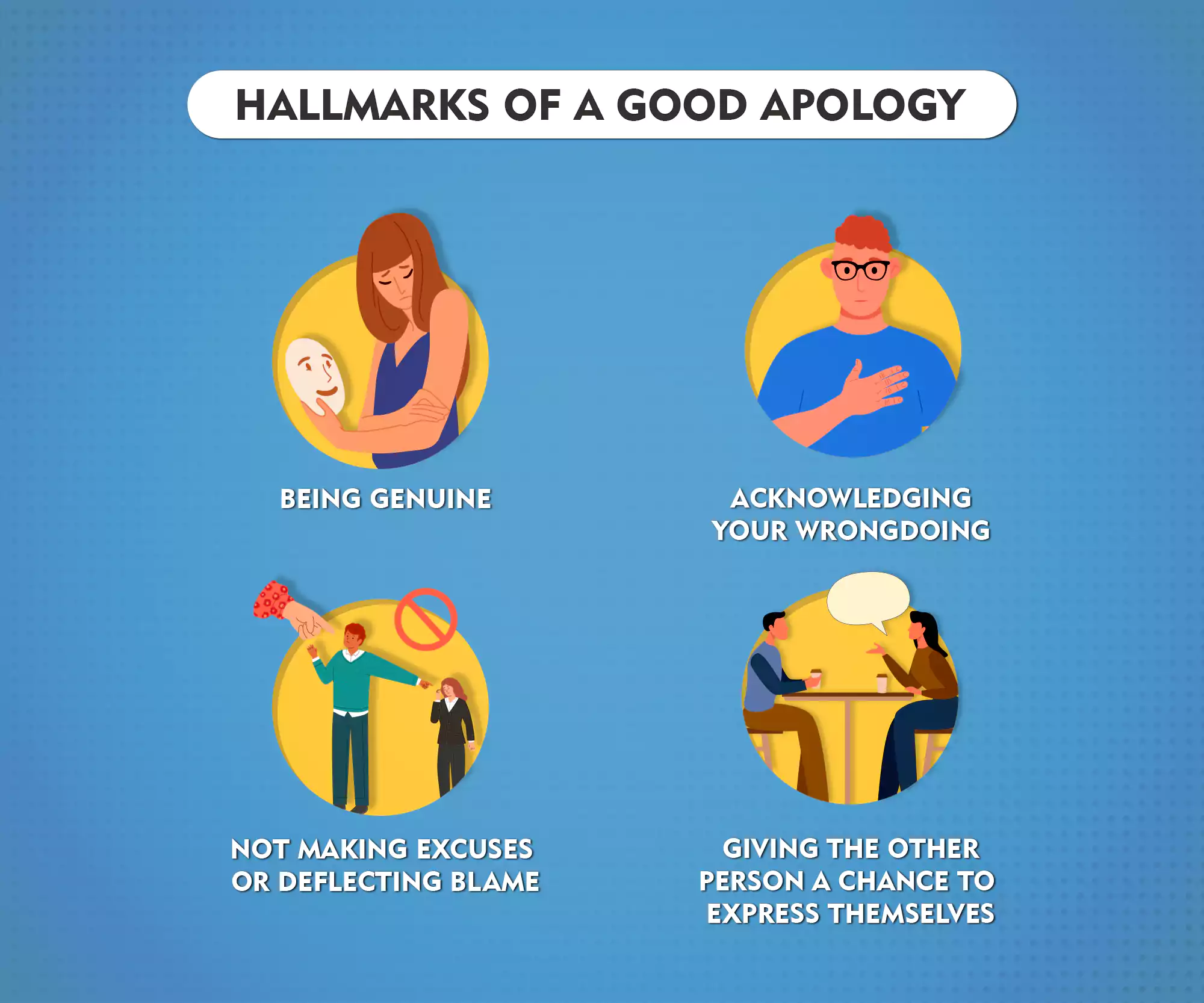

A good apology ought to include a few things. First, remember that an apology’s purpose is to repair a relationship that was injured by whatever had been said or done. Therefore, the first thing a good apology should do is acknowledge one’s part in what happened. I should actively accept what I did wrong without deflecting or making excuses.

The apology must also be genuine. A forced apology won’t be a good one, and people will usually be able to see right through it.

It could also include an explanation for what happened, but only as long as one remembers that reasons and excuses are two very different things. A reason seeks to offer clarity, while an excuse seeks to justify.

Many people tend to go overboard and apologise for many other things when apologising. There is no need to apologise for your entire existence—merely sticking to the point will suffice. However, communicating what happened and how one felt is essential.

One of the most crucial elements of a good apology is recognising that it is not a speech but a dialogue. Therefore, after apologising, we must give the other person the chance to speak and tell us how they feel. Though it is not easy, we must be willing to listen.

Finally, making amends in whatever way possible must also be a part of the process. This process will help to heal what was hurt and strengthen relationships further. Making amends also plays a crucial role in reinforcing the understanding that the offence can never be repeated.

Apologising is difficult, and nobody likes to do it. But, it is an integral part of life that enables us to live and work together in society. The fact of the matter remains that no apology is perfect. An apology will never make everything right. However, a good, heartfelt one will go a long way in making things a little better for everybody involved—no matter the scale of the act. While half-hearted apologies can make things worse, a genuine one—even without all the right words—will always be better than no apology.