After extensive interviews and observations, a UNICEF study on parenting in India revealed that caning, ear-twisting, and slapping were common forms of child punishment. Despite the ban on corporal punishment in the country, the face of discipline in Indian schools and homes is often ugly. So, what distinguishes this type of punishment from abuse? Or from discipline? Or correction? We use many different words to explain, understand, and justify it. However, at the end of the day, we still know as little as when we began. The concept of punishment is vast and includes a world too large to discuss in one article. So, for now, let us think predominantly of punishment and abuse as it relates to children at home and school.

Not the carrot, just the stick

Every so often, school stories surface about the methods the staff employ to punish children. For example, in Nigeria, according to a recent UNICEF report, instances of spanking, slapping, and pinching are common in schools. Many of us have scars—some figurative, others literal—from when we faced the business end of it. We may have been hit with cultured canes or savage sticks, made to kneel outdoors in the hot sun or indoors on frozen peas, stand with arms raised or squat with knees bent for hours on end. These things might sound somewhat familiar to most. And, it is not difficult to find articles or video compilations online.

But, most feel the stick; only a few get to taste the carrot. Don’t get me wrong—those few are inspiring. Like when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez credited her second-grade teacher for steering her towards civil rights movements at a tender age. Still, such stories are too rare.

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words…will definitely hurt me too

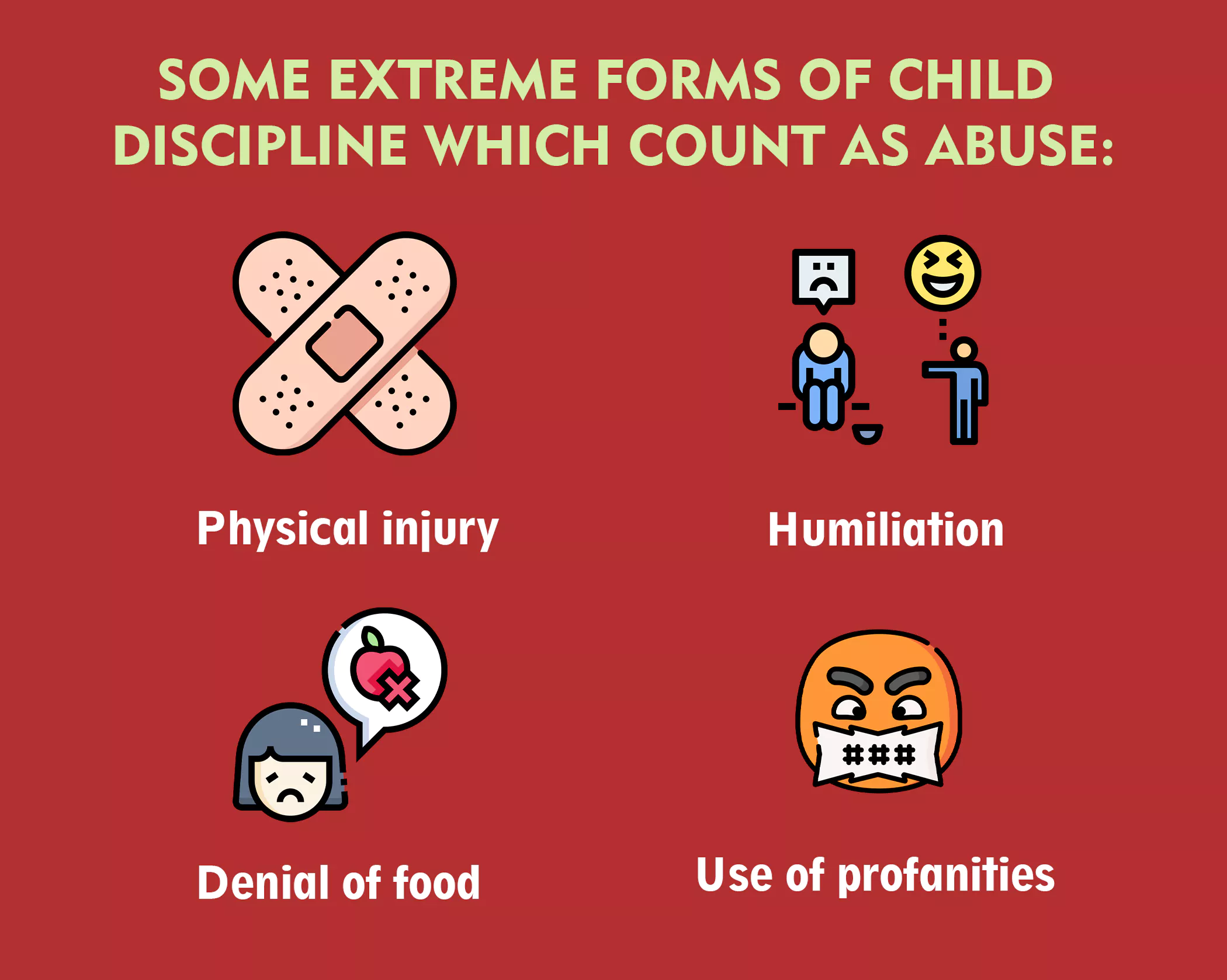

Where physical punishments are frowned upon, many children are subjected to torrents of slurs and shouts, mockery and spite instead. For instance, last year, an elementary school in West Japan dismissed a teacher for verbally abusing students. Sometimes slowly but always surely, this type of verbal abuse eats at a child’s confidence and erodes their self-belief. We cannot consider this abuse better or worse than physically aggressive methods. Both forms of punishment so freely doled out can, given enough time, destroy a human being.

Then, why?

If the results of physical punishment and verbal abuse are so damaging, why do we still engage in them? Why are they allowed? Perhaps that is because it is not usually done in the name of abuse or cruelty but rather in the name of punishment and discipline. As parents, teachers, and adults, we feel tasked with the responsibility of raising children and helping them to grow into well-rounded human beings who fit into society. With that end in mind, when a child misbehaves, we take it upon ourselves to administer some degree of punishment to help the child ‘realise their mistake’ and ‘mend their ways’.

The simple premise behind the idea of physical and emotional violence as punishment is fear. If I can get the child to fear the consequences of an action, they will think twice before acting. However, surely a worldview rooted in fear has stems of insecurity and branches of mistrust.

Or, if you prefer to hear it from the everlasting wisdom of Master Yoda, then “Fear leads to anger, anger leads to hate and hate leads to suffering.”

The conundrum

So, what is the problem? Well, that is the tricky part. The fact remains that it is our responsibility as adults to look after children. We must introduce them to the world we share and help them live in it. A large part of that revolves around learning to live in society with other human beings. That necessarily means performing some actions while refraining from others.

So, how does one help to bring about a sense of discipline without engaging in abuse?

A larger construct

One of the difficulties with discussing punishment and abuse is a subconscious or unconscious refusal to understand that what we do is part of a larger construct. This idea can be challenging to grasp. One way to try and understand it is to look at the same concept in a very different context.

Take racism, for example. Indeed, you know many people who make harmless jokes without considering them to be racist. Or sexism. Small inappropriate touches or comments can hardly be construed as harassment, can they? We tend to be very good at holding clear and crisp ideas about these constructs (even though they may not be universally accepted). But, simultaneously, we are often unable (or unwilling) to see that we might also be engaging in a smaller-scale variant of the same.

And so it goes with punishment and abuse. We tend to think very poorly of people who kick and belt their children. Yet, we are convinced of the moral necessity of pinching and occasionally slapping our own under the disguise of discipline.

We create a world in our minds within which there are good people and bad people. Bad people beat their children—they are deranged and should be imprisoned. Good people discipline their children—they should be lauded. But we refuse to acknowledge that the methods of these ‘good’ and ‘bad’ people are startlingly similar.

We also tend to have an uncanny way of blaming everything on other constructs such as culture and tradition. After all, that is the way it has always been. Our parents hit us, and their parents hit them—this is our culture. Yet, we forget where culture and tradition came from: we made them. We cannot forget that—we are constant creators of culture.

How we justify punishment

“I got hit as a child and turned out fine.”

“It makes people tougher.”

“I do this because I love you.”

“What other way is there?”

Children tend to be incredibly resilient, and they bounce back from most things we throw at them, but does that make it okay to hit them? Abuse doesn’t toughen a child up—it creates calluses so that they don’t feel as much anymore but is that better? And if we are convincing children that we hit them because we love them, think about the ideas about love that it creates in their minds. Would it surprise us to see them ‘love’ others in the same way?

Punishment and abuse within a child’s intimate environment

One of the leading theories in child psychology is Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory of child development. He argues that various spheres of influence exist in a child’s life. Without going into much detail, the microsystem is the sphere closest to the child. It is the only one within which the child can influence and be influenced. That makes it a crucial element in the relationships the child forms and how they develop.

Both the home and the school exist in this microsystem. So, abuse wearing the clothes of discipline can have a critical effect on the child. Then, how do we differentiate necessary discipline from abuse?

Drawing the line between punishment and abuse

That’s just it. Drawing these lines tends to be like drawing lines on water. Some people consider the intent behind the act of punishment as most crucial, while others try to define ‘reasonable force’. The usual recommendations include engaging in dialogue, enforcing ‘time-out’, and setting ground rules upfront. However, even governmental institutions confess that setting the extent of such force can be confusing and often unsuccessful. Between punishment and reasonable force, I don’t entirely know if either is genuinely possible; certainly, neither seems truly sufficient.

So, what other option is there? Being responsible for a child’s growth is hard. I will not pretend to have an answer. Still, perhaps it lies somewhere within the realms of compassion, being a role model, improving communication, and striving to be better for our children.